Field work on the Chilik-Chon Kemin Fault in Kazakhstan

The Chilik-Chon Kemin Fault in Kazakhstan caused one of the largest continental earthquakes ever recorded. In 1889, an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of ~M8.3 occurred on this left-lateral strike-slip fault zone and produced more than 100 km of surface ruptures (Abdrakhmatov et al., 2016). However, not the entire fault ruptured during this event and we know little about its slip rate, a potential segmentation, and past earthquakes. We are interested in this fault for two reasons. First, it is one of the longest faults in this region and detailed knowledge on its behaviour is necessary to understand its role in the tectonic regime. Second, this fault is a threat for Almaty and other cities in the surroundings, including the densely populated area around Lake Issyk Kul. Studying the earthquake history of this fault will help to better understand the seismic hazard it poses.

An EwF team did field work on this fault for two weeks in July and August, supported by a travel grant from COMET. Christoph Grützner (Cambridge), Angela Landgraf (Potsdam), and Aidyn Mukambaev (Almaty) wanted to find out more details about the tectonic geomorphology of this fault zone and studied the slip rate and earthquake recurrence intervals.

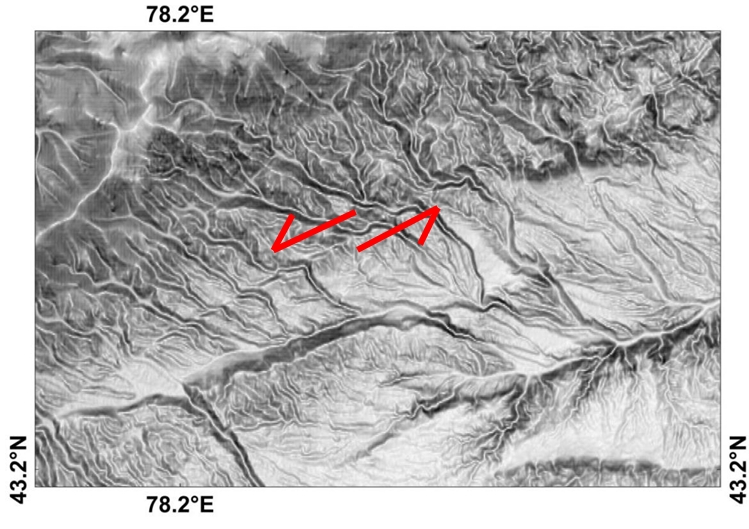

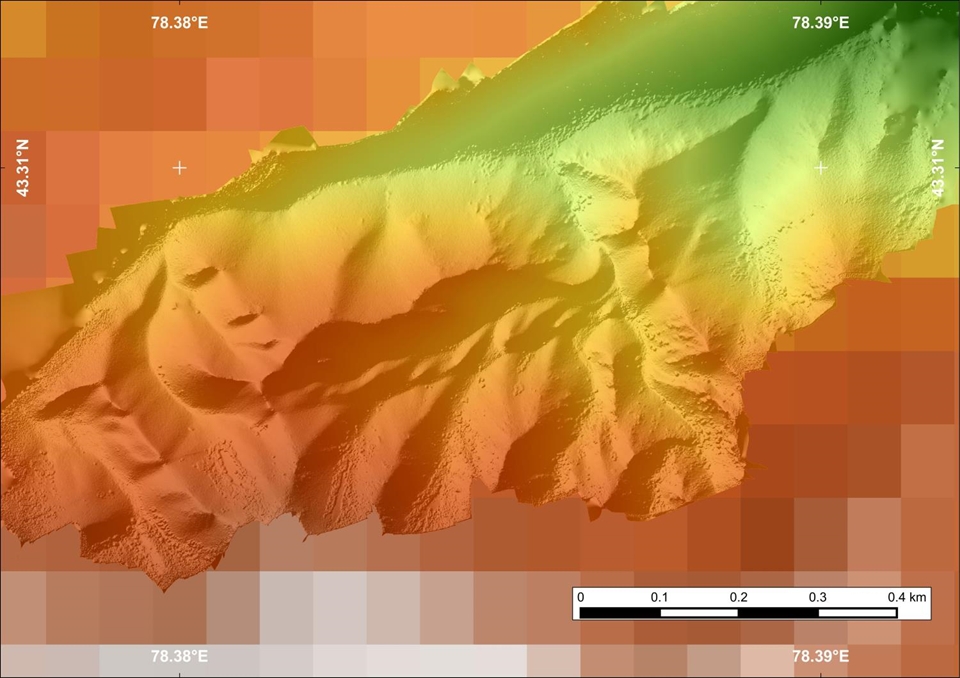

The fault has a very prominent morphological expression. Offset valleys and ridges can be seen on satellite imagery. For measuring the offset precisely we needed a better dataset, though. We bought stereo Pléiades imagery to compute a high-resolution digital elevation model (DEM) for this purpose.

We used stereo Pléiades imagery to produce a good DEM. The data reveal traces of active faulting in the landscape.

This DEM allows us to identify even faint hints of faulting in the landscape. In the field we used aerial photos that we took with our drone to produce even higher-resolution datasets of the sites we were most interested in.

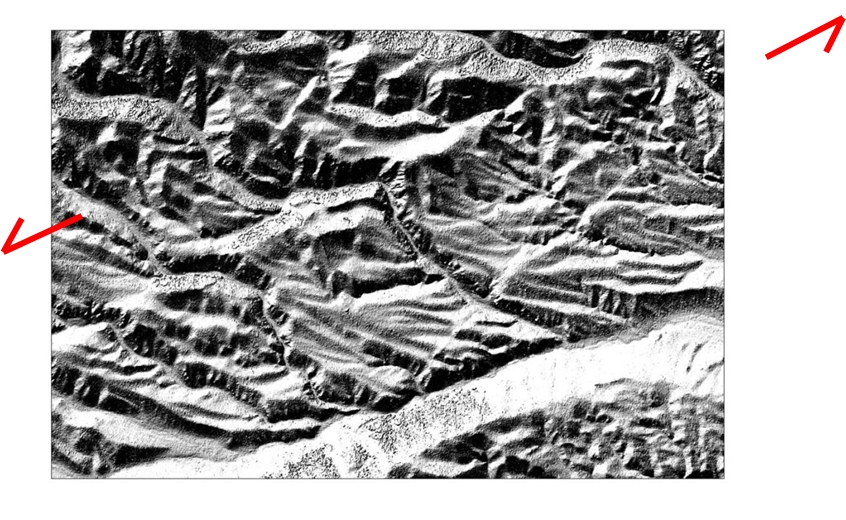

We discovered offset channels and windgaps that testify to a vertical component of motion on the Chilik-Chon Kemin Fault. In some areas we found scarps that offset relatively young surfaces. This tells us that a surface-rupturing earthquake happened in the past few thousands of years.

The fault offsets ridges horizontally and vertically. Its vertical component of motion caused the mountains on the left to be uplifted.

A windgap – a former river valley which was uplifted by tectonic activity and consequently abandoned by the river.

We dug trenches across these scarps in order to find offset sediments that we can date. In the trenches we found old soils that can be dated with radiocarbon. We also collected OSL (optically stimulated luminescence) samples which can be used to find out for how long the sediment has been buried – this is turn allows us to determine the age of alluvial fans and other material.

At present we are analysing the DEMs that we collected and we are waiting for our samples to be shipped to the UK. Hopefully we will get some good dates from them very soon.

Apart from the scientific importance of the Chilik-Chon Kemin Fault we were also stunned by the beautiful landscape and by the hospitality of the locals who helped us. Our study sites were very remote with the next market 3 hours away, so we were happy to stock up our supplies with fresh milk, cheese, cream, and lamb.

A big thank you to our driver and cook who made this field work a pleasure! Our colleague Kanatbek Abdrakhmatov from Bishkek organised the logistics and taught us a lot about the geology of the Tien Shan.

Further reading

- Abdrakhmatov, K., Walker, R. T., Campbell, G. E., Carr, A. S., Elliott, A., Hillemann, C., Hollingsworth, J., Landgraf, A., Mackenzie, D., Mukambayev, A., Rizza, M., and Sloan, R. A., 2016. Multi-segment rupture in the July 11th 1889 Chilik earthquake (Mw 8.0-8.3), Kazakh Tien Shan, interpreted from remote-sensing, field survey, and palaeoseismic trenching; JGR-solid earth, 121, doi: 10.1002/2015JB012763.