A trip to the end of the world …

Our field seasons in central Asia have taken us to all kinds of remote and spectacular places, but nowhere really compares to the Alai valley of southern Kyrgyzstan. Here, the Tien Shan and Pamir, two of the greatest mountain ranges on Earth, come together across a narrow valley. The wall of the Pamir stretch as far as the eye can see, and driving towards them it feels as though you have reached the end of the world. In August 2014 I took the opportunity at the end of our fieldwork to travel overland to the Alai to examine the active thrust fault on which the Pamirs are growing.

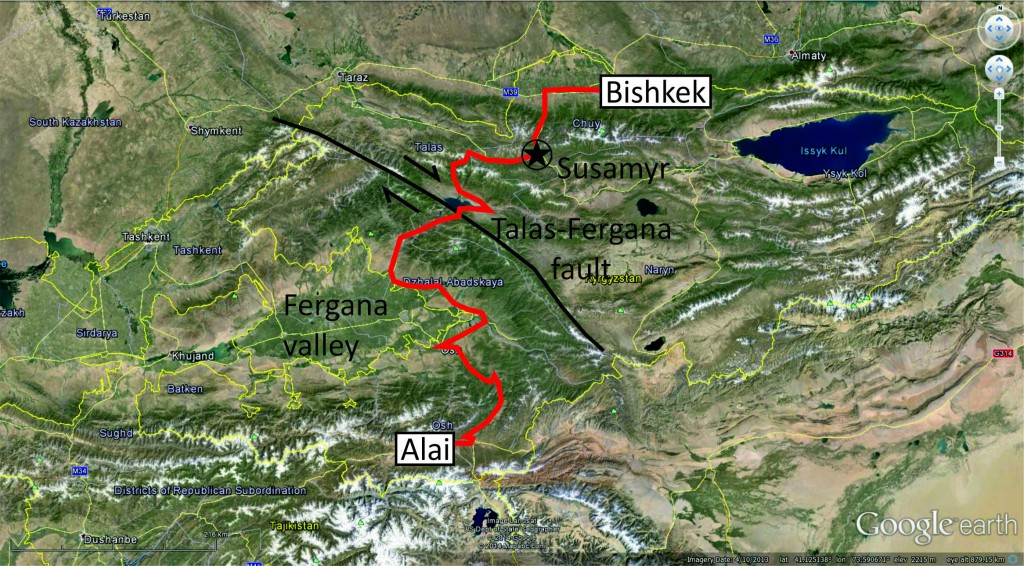

The road from Bishkek to the Alai valley is long, mountainous, and took us past numerous reminders of the region’s natural hazards. Heading west from the city the road passed through the epicentral area of the 1885 Belovod earthquake, which ruptured part of the northern edge of the Kyrgyz Tien Shan range. The road then took us up and over the Kyrgyz range, to drop down into the Susamyr valley, which was the site of the most recent large earthquake in Kyrgyzstan in 1992, and where we stopped to examine the fresh ruptures.

From Susamyr, a long drive took us to the Toktogul reservoir and a crossing through the Fergana range, where we encountered a spectacular roadside section through the Talas-Fergana fault. This fault is one of the longest and most prominent in the geology and geomorphology of the Tien Shan, and yet its slip history and potential for earthquakes is not well known.

Crossing the Fergana range the temperature rapidly warmed as we dropped down to the cotton fields of the Fergana valley. This almond-shaped depression is surrounded on all but its western edge by high mountains, which provide plentiful water for irrigation, but which are gradually consuming the basin by slip along reverse faults at their margins. We were treated to wonderful roadside sections through multi-coloured basin sediments folded and deformed above the growing faults. Some of the folds have trapped hydrocarbons, which are exploited to the present-day.

After skirting the Fergana valley, the road headed south, into the high mountains. We passed through narrow gorges of Palaeozoic granite and gneiss, interspersed here and there with thin rainbow smears of tertiary sediment marking the consumed remnants of what were once wide basins, providing roadside snapshots of the deeper history of the Tien Shan. Eventually, the road started towards a wall of limestone peaks, climbing rapidly up a series of tight switchbacks to a pass into the Alai valley at 3,600 m.

The present road is pretty new, but sections of the steep mountainside into which it is built are already showing signs of collapse. The road is very important though, as it from the Alai valley its splits, and crosses high passes to connect with both Tajikistan and China. From a distance you are hard pressed to see where the passes to Tajikistan are, as the first view on entering the Alai valley is of a continuous wall of icy mountains as far as the eye can see. This is the north wall of the Pamir, which reaches up to the 7,134 m summit of Peak Lenin.

There is about four kilometres of relief between the summit of Lenin Peak and its base in the Alai valley (at 3,000 m elevation). At the southern edge of the valley is the trace of the Main Pamir thrust. This fault accommodates 5-6 mm/yr of shortening between the Pamir and Tien Shan (Arrowsmith and Strecker, 1999) making it one of the major active faults in Asia. We were impressed by the freshness of the fault scarp, and also by how rapidly the landscape has changed over the past few thousand years in this high-elevation environment. The Pamir thrust also contains a lesson for the mapping of earthquake hazard. Although it is amongst the fastest active faults of central Asia, there are few large earthquakes recorded upon it, presumably a function of the short historic record. A full appreciation of active faults and their ability to produce destructive earthquakes thus requires careful mapping of their expression in the landscape, combined with forensic investigation of ancient earthquakes from their expression in recent sediments.