(See Publications tab for published outputs, and the Blogs tab for reports on particular fieldwork expeditions)

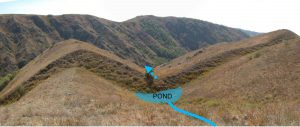

Surface offset of about 10m on the Lepsy fault in the Dzungar Alatau of Kazakhstan, from an earthquake about 400 years ago (Campbell et al 2015). Sediments ponded against the fault from a blocked stream allow dating of the last movement. Photo: James Jackson.

Kazakhstan has been a particular focus of the EwF project, with much exploratory work on the earthquake hazards and the perceptions of them by those exposed to them. Original geological fieldwork on identifying and characterizing the active earthquake faulting has been mainly in the region from SW of Almaty to Usharal in Dzungaria, investigating faults both within the Tien Shan and in its foreland. Particular attention has concentrated on clarifying the likely faulting responsible for the destructive earthquakes of 1887, 1889 and 1911, which affected the Almaty and Chilik regions. Our principal collaborators have been the Institute of Seismology and the Kazakh National Data Center. Social Science fieldwork has been mainly near Taraz, Shymkent and the Talgar Valley, and has been principally concerned with risk perception; and important aspect of resilience that resonates throughout the EwF project, emphasizing the difficulties of prioritizing the apparently-remote threat of earthquakes in competition with the more obvious and pressing everyday concerns and hardships of urban and village life in Asia. Our main collaborators in these aspects have been the Red Crescent Society, the Kazakhstan Buildings Institute and Taraz State University.

In September 2016 EwF co-hosted a 3-day conference in Almaty with the Institute of Seismology and with support from the Akimat’s (Mayor’s) office and the sponsorship of the Yessenov Foundation. The meeting brought together earthquake scientists in the EwF partnership from the UK, Italy, Germany, Iran, India, Nepal, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and China, to interact with Kazakh scientists and policy makers to encourage the development of earthquake science and discuss how to use scientific knowledge to help increase earthquake resilience in central Asia. It included vigorous debates on practical issues of public awareness and education as well as on the dangers in allowing any belief in short-term earthquake prediction to be linked to policy on public safety. A booklet summarizing the content and resolutions adopted at the end of the meeting has been published: and is also available in Russian.

Surface faulting from the 1911 Chon-Kemin earthquake in Kyrgyzstan, which badly damaged Almaty, 50 km away in Kazakhstan (photo: Richard Walker).

Kyrgyzstan has also featured prominently in EwF research, with many active faults in the Tien Shan crossing international border with Kazakhstan. Geological fieldwork has focussed on the region from Naryn, Suusamyr and Issyk Kul, with a view to establishing the fault patterns, distributions and slip rates between the northern Tien Shan range front and the Chinese border in the south. In both Kyrgyzstan and SE Kazakhstan the active faulting is distributed across the range, rather than concentrated at the topographic front. Our principal collaborator is the Institute of Seismology in Bishkek, with its Director, Prof. Kanatbek Abdrakhmatov participating in most of our fieldwork in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. In October 2017 EwF delegates from UK, Nepal and Iran participated in a workshop in Bishkek run by the Association of Academies and Societies of Sciences in Asia on Joint efforts to reduce the Risks and Consequences of Earthquakes, Bishkek.

Uzbekistan also suffers from earthquakes, and the destruction in the 1966 earthquake at Tashkent is vividly remembered. A preliminary investigation of a prominent active fault system east of Tashkent has taken place, and we anticipate completing this work soon. Our collaborator is the Academy of Sciences.

Scarp, about 2m high, from an historical earthquake on the Kopet Dag fault NW of Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. Samples have been collected from a trench site to date the last surface movement on this fault. Photo: James Jackson

Turkmenistan: we have now completed three successful field investigations of the Kopet Dag range front from Ashgabat NW towards the Caspian Sea, jointly with the Institute of Seismology in Ashgabat. Attention has focussed on the prominent recent earthquake scarps along the main Kopet Dag strike-slip fault, which has been mapped and associated geomorphological features dated, in order to establish both the Late Quaternary slip rate and the date of the last earthquake. There is a pressing need for such research as the fault responsible for the catastrophic 1948 earthquake, which destroyed Ashgabat, is uncertain. We have also started to work on the area adjacent to the Caspian Sea, where earthquakes are deeper (typically 30-40 km), yet are still associated with surface faulting and active geomorphology.

Mongolia: we have long-standing interests and research collaborations in Mongolia, going back at 20 years. Research has concentrated on geomorphology and paleoseismology of active faulting in the Gobi-Altay, Mongolian Altay and Hungay regions, with principal collaborators from the Mongolian University of Science and Technology, Ulaanbaatar.