Landslides following the 2015 Gorkha earthquake: Monsoon 2016

Observations

The 2015 Gorkha earthquakes triggered more than 22,500 landslides, focused along the major river valleys in the hill and mountain districts of central and western Nepal, and were equivalent to several hundred years of ‘normal’ monsoon-triggered landslide activity in these districts. The 2015 monsoon caused numerous additional landslides, focused in the areas that were hardest-hit during the earthquake, and at rates that were still 10-20 times greater than a normal monsoon. The 2015 monsoon also reactivated many of the landslides that were triggered by the earthquake, generating highly mobile debris flows (mixtures of sediment and water) that have travelled long distances downslope during intense rainstorms.

The 2015 monsoon strength was widely considered weaker than normal. As expected, during the dry season (October 2015 – June 2016), few landslides have changed. The 2016 monsoon is forecast to be normal, and so more intense than 2015, and so landsliding is expected to be as, if not more, severe in 2016. Furthermore, areas with the greatest degree of landslide activity in the earthquake and the 2015 monsoon will be at greatest risk of further landsliding, including debris flows, during the 2016 monsoon.

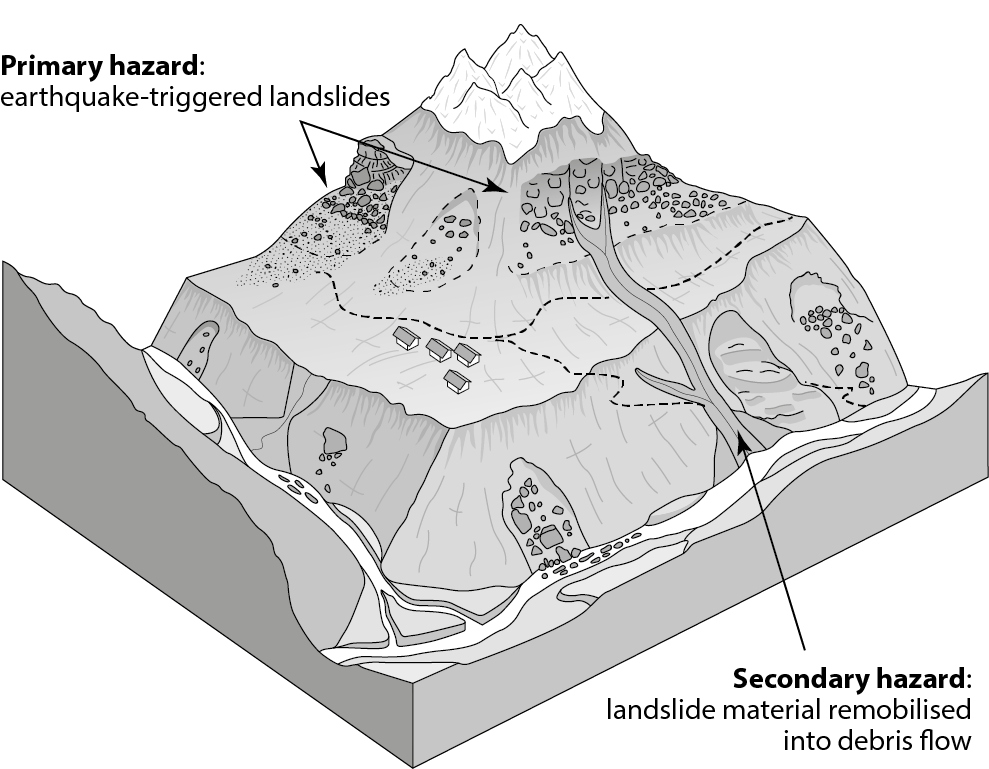

Landslides – both those triggered by the earthquake, and by subsequent rainfall – pose two forms of hazard to people and infrastructure (Fig 1):

- Primary hazard associated with the direct impact of continuing landslides and rockfalls. This is focused below steep slopes, both along valley floors and higher in the landscape. Pervasive cracking has been observed across the affected districts, suggesting many slopes remain unstable.

- Secondary hazard associated with rapid debris flows. During intense rainfall, unstable material that is perched high in the landscape can be mobilised and flow to the valley bottom, posing a considerable risk to those in the valleys below. This is focused along and immediately adjacent to (typically within 50 m) pre-existing drainage channels, with flows travelling large distances (multiple km).

Fig 1. Schematic view of landslide hazards in earthquake-affected mountain districts of Nepal after the 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Landslides triggered by the earthquake (primary hazard) are focused high on hillslopes (typically above most settlements) and along valley floors. Landslide material is then remobilised into debris flows (secondary hazard) that travel down along existing channels or gullies and affect valley floors.

These different types of hazards have very different impacts and require different mitigation measures. Both forms of hazard, however, increasingly have major impacts on the densely populated, valley bottom settlements, adjacent to major transport corridors. Whilst it is effectively impossible to predict the exact locations of the primary hazard, simple rules of thumb can be used to identify the most risky locations:

- areas below steep rock faces or loosely consolidated material

- areas with previous evidence of landslides (e.g. missing or thin vegetation on hillslopes, fresh boulders on roads, cracks in roads)

- locations beneath slopes that naturally funnel falling material toward a single point

- areas where water is flowing out onto the road surface

- areas beneath un-engineered road cuts

- stream channels of any size, particularly where water is coloured by fresh sediment

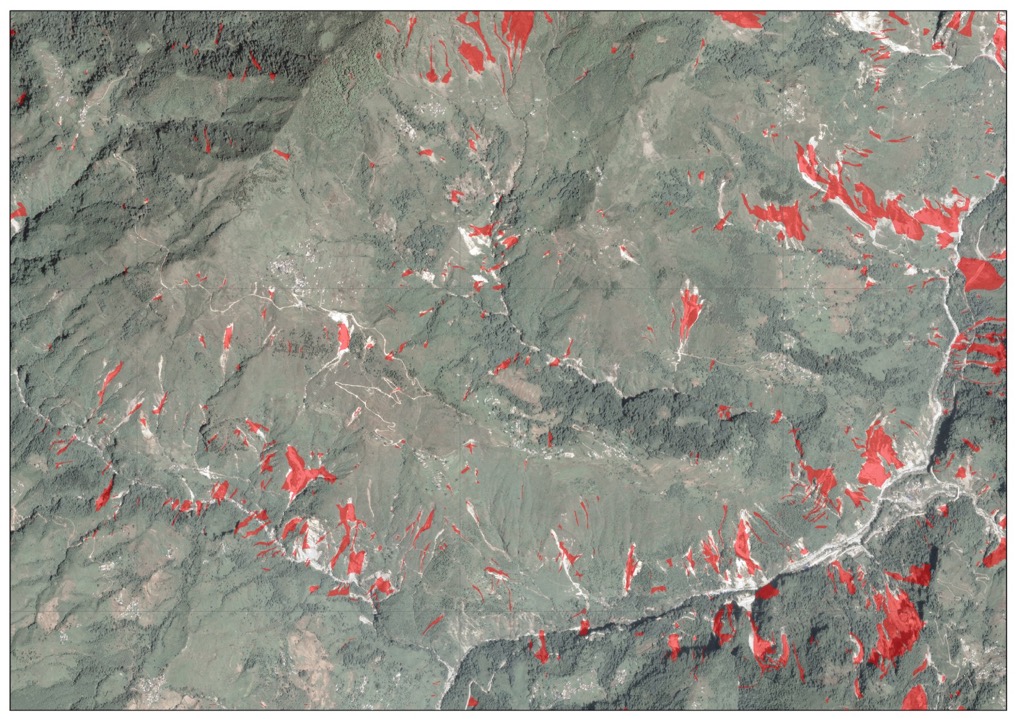

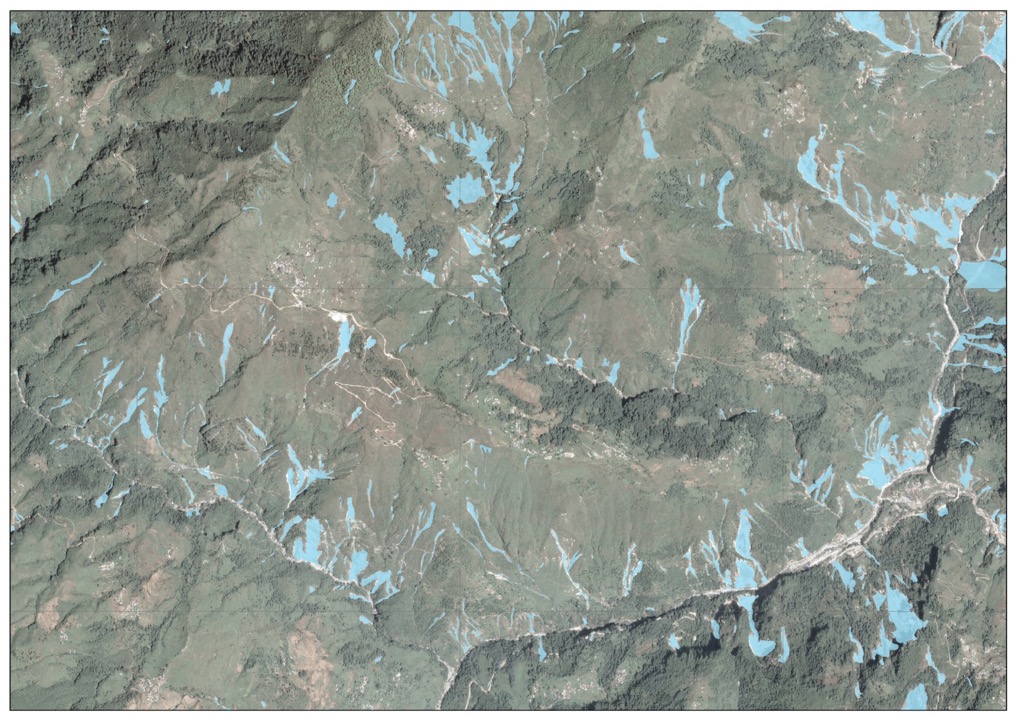

Observations from the earthquake affected districts, along with direct comparative experiences from the 1999 Chi-Chi, 2005 Kashmir, and 2008 Wenchuan earthquakes, shows that landslides and debris flows will occur at higher-than-normal rates in the earthquake-affected area for the next years to decades. The districts shaken by the earthquake still have many areas of cracked ground (Fig 2), which may develop into landslides during the monsoon, as seen during the 2015 monsoon from the analysis of repeat satellite images (Fig 3 – 4). Monitoring of these districts and analysis of how landslides are changing since the earthquake is, to date, inconclusive about the future risk. It is not currently possible to be more precise about the duration of this enhanced landslide activity, and it is likely to vary with both location and monsoon strength.

Fig 2. Extensive ground cracking in Listi VDC, Sindupalchok.

Importantly, it should not be assumed that the hazards described above are ‘finished’ and are no longer an issue in 2016 or later. Indeed, areas which have previously experienced a landslide are highly likely to experience further landslides. Quiescence during the dry season is not an indication of future stability during the monsoon. The nature of landslide hazard will evolve, and there is no precedent for how this will play out, so monitoring how this evolves is important to assess risk.

Fig 3. The extent of landsliding triggered by the 2015 earthquakes, shown by red polygons. Area shown is Listi VDC, Sindupalchok. Image width is c. 6 km.

Fig 4. The extent of landslides after the 2015 monsoon, showing an increased occurrence of landsliding reaching the valley bottoms. Area shown is Listi VDC, Sindupalchok. Image width is c. 6 km.

2016 South Asian Summer Monsoon

The World Meteorological Organisation publishes the consensus outlook for the South Asian Summer Monsoon in April[1]. In summary, El Niño conditions have weakened, and are predicted to continue to weaken over the summer, with La Niña conditions developing later in the season. Comparison with historical records suggests that such conditions are coincident with normal and above-normal rainfall over the South Asia region. In Nepal, it is predicted that the 2016 monsoon will generate near-normal rainfall over the majority of the country, including the earthquake-affected districts, with above normal in the far south west and below normal in the east. If La Niña conditions to develop later in the season, increased levels of rainfall may be expected.

From the perspective of landslide risk, this forecast suggests a stronger monsoon than 2015, and so a heightened risk from rainfall-triggered landslides in 2016. Landslide risk relates to both: (i) a long-term build-up of moisture in the ground through the monsoon period, and (ii) extreme intensity short-duration rainfall. Both conditions can generate hazardous landsliding. The monsoon onset in Nepal is normally expected on 10th June with the cessation on 23rd September. Whilst intense pre-monsoon rainfall in early May has already triggered several fatal landslides in Nepal (e.g. Kotwada VDC, Kalikot, 20th May) and led to some road blockages (e.g. the Arniko Highway on 20 and 24 May), the 2016 monsoon onset is widely regarded to be delayed.

Key messages: Reducing risk to landslides

Whilst it is effectively impossible to negate the risk posed by landslides in Nepal, simple measures can reduce exposure:

- Refer to weather forecasts when planning travel (e.g. http://www.bbc.co.uk/weather/)

- Avoid all travel during rainfall, and plan around predictable daily afternoon rains

- Avoid all travel in darkness to reduce the chance of collision with recent landslide debris

- Reduce time spent in hazardous locations (see above)

- Do not cross recent landslide deposits to reduce the risk of being stranded in exposed locations

- If vehicle is stranded near a road blockage, wait in a safer location (see above)

- Assume that those VDCs most heavily impacted by landsliding in 2015 will be those most susceptible to future landsliding in the 2016 monsoon

- Seek local advice on condition of road ahead and areas of recurrent landslide problems

- Be aware of potential recurrent blockages that may inhibit return journey

Nick Rosser, Alexander Densmore and Katie Oven, Durham University

June 2016

[1] http://ane4bf-datap1.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/wmocms/s3fs-public/consensus_statement_sascof8-1.pdf?CUSH5v4GMJHw9E7BJYTp1I7OpfHnbVSL