Active faults in northern China and some rather cold fieldwork

By Tim Middleton, PhD student at COMET+, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford

Inner Mongolia is cold in November. Snow and ice blanket the elevated plateau and the biting winds drag the temperature well below minus 20°C. An enormous wind farm, recently installed by the local government, makes good use of the extreme weather. Herdsmen are dressed in fur coats and ski goggles, whilst other locals hack at frozen bales of hay with pickaxes. Perfect conditions, then, for a field trip examining the active faults!

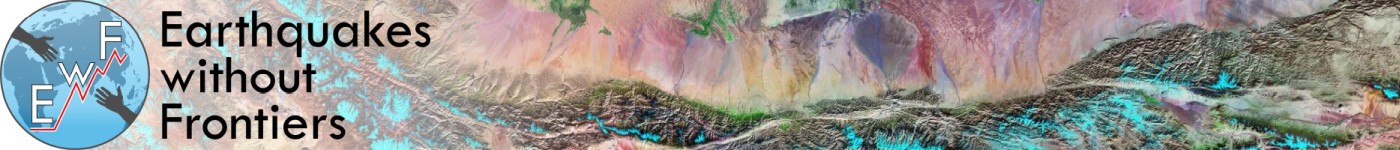

Figure 1: East-west strike-slip fault in Inner Mongolia with a small component of vertical motion to produce the scarp visible in the photograph (possibly the result of a single palaeo-earthquake rupture). The fence crossing the scarp clearly indicates the height difference. Drainage has ponded against the scarp leading to greater vegetation cover on the northern side of the fault.

At the end of November 2012 a small group of researchers (Dr. Richard Walker from the University of Oxford, Dr. Weitao Wang from the Institute of Geology at the Chinese Earthquake Administration and I) spent a busy week doing reconnaissance fieldwork in northern China. We were particularly interested in two things: the possible presence of active strike-slip faults in Inner Mongolia (the northernmost province in central China), and the determination of slip rates on the active normal faults in the northern Shanxi grabens.

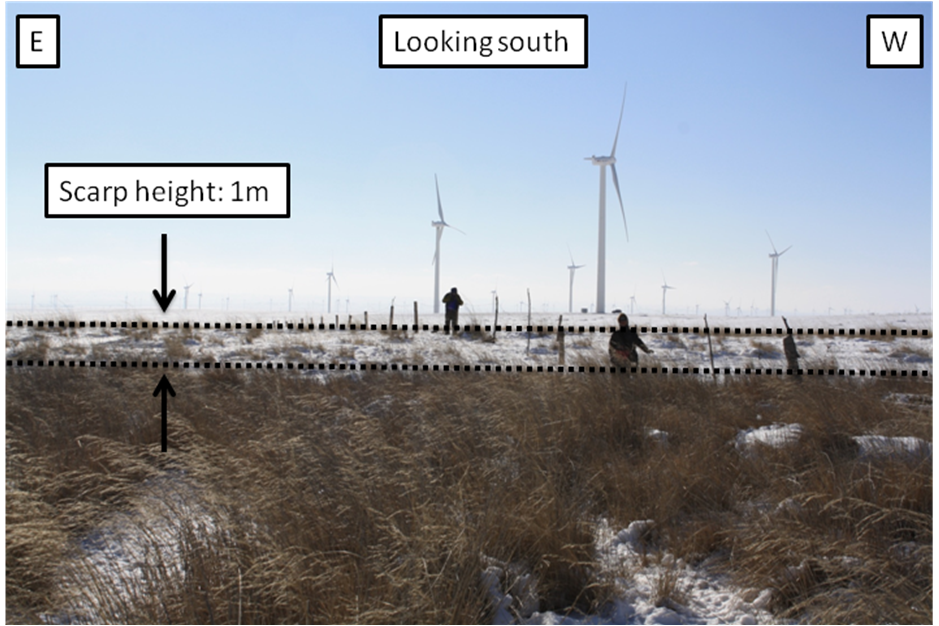

Figure 2: Topographic map of north central China. Beijing is just visible on the eastern edge of the map. Topographic data is from ASTER GDEM; GPS data is from Wang et al., 2002; focal mechanisms are from the CMT catalogue. Black lines indicate active faults and are drawn with the aid of topographic data and satellite imagery. A major strike-slip fault is visible to the northwest of the map, whilst the northern Shanxi grabens are shown towards the south of the map.

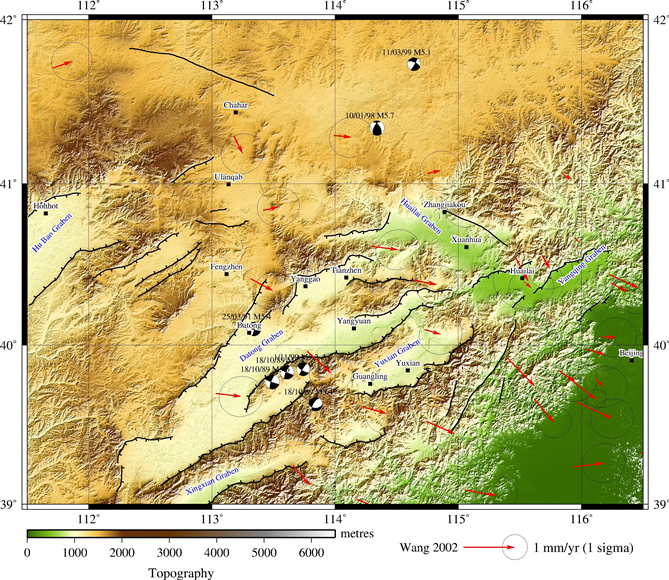

Up on the Inner Mongolian plateau, large areas are covered by Cenozoic basalt flows and the landscape is spotted with volcanic cinder cones. A number of the faults cut these flows and by determining the ages of the basalts we hope to be able to place constraints on the rate of motion of these faults. It is also interesting to note that the majority of the cinder cones form belts that trend northeast-southwest, parallel to the normal faults in the northern Shanxi. Tapponnier and Molnar (1977) suggest that this is to be expected given the overall northwest-southeast extension in the region.

Figure 3: Northeast-southwest trending basaltic cinder cones. The same cones were visible from the window of our plane as we flew into Beijing!

After our sojourn to the freezing north, we moved south to the relatively balmy minus 5°C of Hebei and Shanxi provinces to visit the northern Shanxi grabens. This graben system constitutes the northern portion of the extension that is occurring along the eastern edge of the Ordos Plateau. It comprises a mixture of complete grabens—with intervening horst blocks—and tilted half grabens.

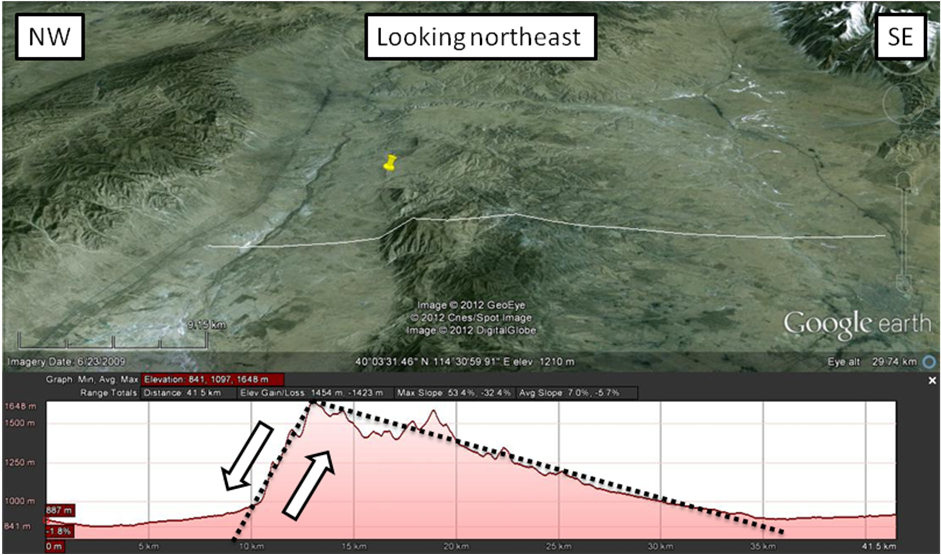

Figure 4: Topographic profile across the footwall of the fault on the southeastern side of the Datong Graben. The profile clearly shows the classic tilted block morphology expected of a half graben.

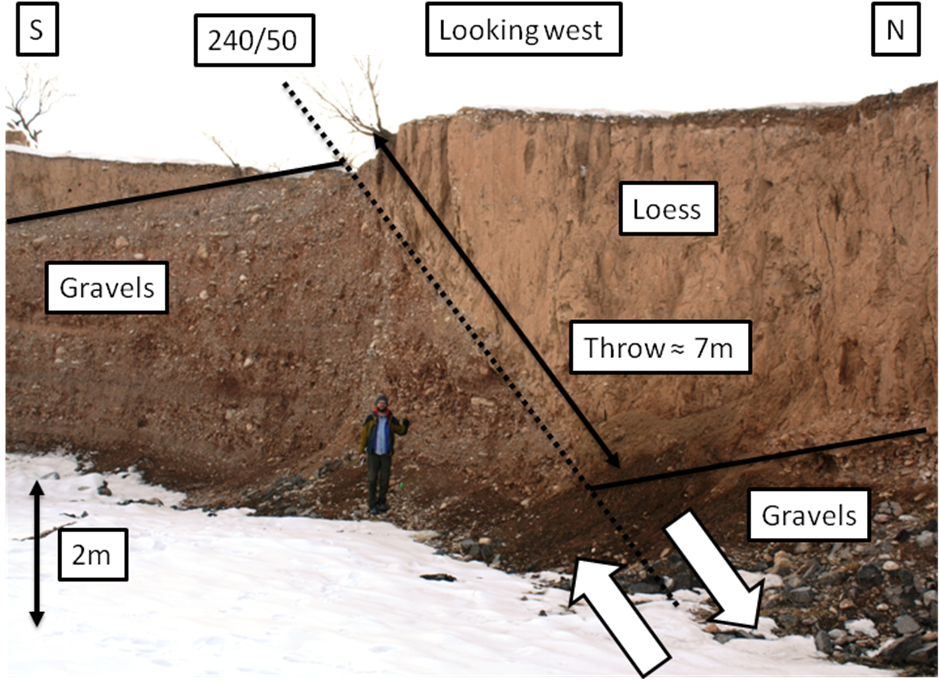

We visited graben-bounding faults on the northwest side of the Datong Graben, the southeast side of the Datong Graben and the southern side of the Yuxian Graben. At each site we took samples from loess deposits immediately overlying uplifted river gravels in the footwalls of the faults. By using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating, we hope to be able to determine the rates of motion on these faults. In some locations we even found exposed sections of the fault plane, allowing us to measure its strike and dip. This will enable us to convert our vertical rates of motion into slip rates in the plane of the fault.

Figure 5: Exposed normal fault on the southern side of the Yuxian Graben. The contact between river gravels and the overlying loess is visible on both sides of the fault, allowing us to estimate the throw on this portion of the fault.

Along one arm of the Datong Graben the topographic data suggests that a new fault is growing in the centre of the basin. We drove past one evening and were rewarded with a stunning sunset view of the fault scarp, looking across the Sanggan River.

Figure 6: Sunset over the Sanggan River. The river is important because it supplies much of Beijing’s water. It also features in Ding Ling’s 1948 novel “The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River”, a reflection on the life of peasants at the time of land reform in northern China.

Few earthquakes have severely affected this part of China in recent history, but the faults we saw on this trip show clear evidence of Quaternary activity. Hopefully we will be able to learn a lot more about them on future trips—perhaps when it’s slightly less cold!

With thanks to Dr. Weitao Wang and the Institute of Geology at the Chinese Earthquake Administration.